Metoidioplasty.net » Metoidioplasty Procedures

Ring Metoidioplasty

Ring Metoidioplasty, also known as Ring Flap Metoidioplasty, is a technique developed in Japan by Dr. Ako Takamatsu that was first performed in 2006. This method creates a small phallus using clitoral release and tissue flaps from the labia minora and anterior vaginal wall, enabling standing urination and preserving erotic sensation. Unlike other Full Metoidioplasty techniques, Ring Metoidioplasty does not require buccal mucosa grafts or vaginectomy, which makes it a lower-risk alternative.

How It Works

Ring Metoidioplasty uses only local genital tissue to construct both a neophallus and a functional urethra. Unlike the Belgrade method, it does not require a second donor site, such as the inner cheek (buccal mucosa), eliminating risks like oral pain, dry mouth, and donor site scarring.

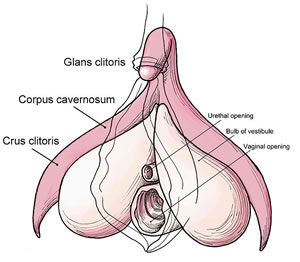

During the procedure, the clitoral chordee (tight connective tissue that restricts projection) is released to straighten and lengthen the hormonally enlarged clitoris. A ring-shaped flap is created using the inner surfaces of the labia minora, and an additional flap is taken from the front part of the vaginal wall. These are joined and tubed around a catheter to form a neo-urethra, enabling standing urination for most patients.

In contrast to the Belgrade method, Ring Metoidioplasty does not include vaginectomy. Instead, the vaginal opening is reduced but the canal remains intact. This allows for a shorter procedure with less tissue disruption, but won’t meet the needs of those seeking vaginectomy.

In Takamatsu’s technique, the suspensory ligament is not mentioned as being released. A modified version of the procedure, developed by Dr. Mang Chen and colleagues in the U.S., takes additional steps to preserve blood flow to the newly created urethra. In this version, suspensory ligament release, monsplasty, and labial fold reduction are intentionally delayed until a second stage, typically 4–6 months later. This protects the anterior pedicle, which supplies the urethral flap, and helps reduce complications like strictures or necrosis.

A suprapubic catheter is placed during surgery to divert urine while the urethra heals. Cosmetic refinements, such as scrotoplasty, testicular implants, and mons resection, are generally performed in a second-stage procedure, depending on patient preference and healing.

Watch Dr. Brad Figler perform Ring Metoidioplasty and see the surgical results in this detailed academic video. Please note: The video contains graphic surgical content. Sign-in to verify age required.

- Operative Technique Overview: Watch Video

Expected Results

Ring Metoidioplasty produces a small but functional penis with preserved sensation, added girth, and the ability to urinate while standing for most patients. While the neophallus is not usually large enough for penetrative intercourse, many patients report improved comfort, gender congruence, and sexual satisfaction. Since no buccal graft is required, oral healing complications are avoided. The retained vaginal canal may be a consideration for some, although its opening is narrowed.

Risks and Complications

Like all gender-affirming surgeries, Ring Metoidioplasty carries some risk of complications. The most common is a urethral fistula, with a reported rate of approximately 8–9%. In some cases, these fistulas resolve spontaneously. When surgical repair is needed, it is often an outpatient procedure.

Other potential complications include:

- Urethral stricture

- Minor wound healing delays

- Dissatisfaction with phallic length or contour

Because no second donor site is used, overall recovery tends to be a bit easier than techniques involving buccal grafts.

Complementary Procedures

Ring Metoidioplasty may be followed or complemented by:

- Hysterectomy (optional, can be performed at the same time)

- Vaginectomy

- Scrotoplasty with testicular implants

- Mons resection and penile repositioning

Since suspensory ligament release and labial tissue excision are delayed to preserve urethral blood supply, they are incorporated into the second stage of surgery.

Who Is This Procedure Right For?

Ring Metoidioplasty is a good choice for transgender men and nonbinary individuals seeking a procedure that offers standing urination and preserved sexual sensation. It may appeal especially to those who want to avoid oral mucosa harvest and vaginectomy.

Because vaginectomy is not performed, it’s not suitable for patients who want complete removal of the vaginal canal. Additionally, some individuals may prefer other techniques if they desire more immediate scrotoplasty or ligament release.

Recovery

Recovery time varies depending on the scope of surgery. Most patients have a Foley catheter and may also receive a suprapubic catheter to support urethral healing. Hospitalization is generally short, and most patients return to light activity within 2–4 weeks.

Secondary procedures such as scrotoplasty and monsplasty are typically performed 4–6 months after the initial metoidioplasty. Complete healing of the urethral extension is monitored over time, and minor revisions may be required.

Surgeons

This procedure is currently performed by:

- Dr. Toby Meltzer – Scottsdale, Arizona, USA

- Dr. Mang Chen – San Francisco, California, USA

- Dr. Loren Schechter – Chicago, Illinois, USA

- Dr. Brad Figler - Hillsborough, North Carolina, USA

- Dr. Marci Bowers – Burlingame, California, USA

Other surgeons may perform modified versions of this technique, often in combination with Ghent-style scrotoplasty, vaginectomy, and perineal masculinization (perineoplasty). For example, Dr. Meltzer's Metoidioplasty method is a modified Ring technique that uses labial flaps for the urethroplasty instead of the vaginal wall flap and also includes vaginectomy.

Journal Articles

- Demzik A., Snyder L., Hayon S., Chen M., Figler BD. (2021). Ring Flap Metoidioplasty. Urology, Volume 158, December 2021, Page 243.

- Meltzer TR, Esmonde NO. Metoidioplasty using labial advancement flaps for urethroplasty. Plast Aesthet Res. 2020;7:61. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/2347-9264.2020.122 [FULL TEXT]

- Takamatsu A., Harashina T. (2009). Labial ring flap: a new flap for metoidioplasty in female-to-male transsexuals. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. [FULL TEXT]

- Takamatsu A., et al. (2001). Beginnings of Sex Reassignment Surgery in Japan. Int J Transgenderism, Volume 5, Number 1. [FULL TEXT]

Last updated: 06/02/25